|

|---|

by Joanna Klonsky

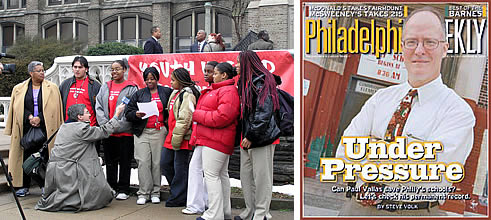

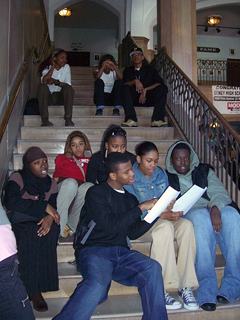

PHILADELPHIA—On a mid-February afternoon, 35 students from the small schools housed in Kensington High School in north Philadelphia gather around a table in their meager school library. Most came because they saw a flier advertising free pizza at a meeting of an organization called Youth United for Change. But it soon becomes clear that this meeting is about much more than an after-school snack.

As Youth United for Change (YUC) Executive Director and Organizer Andi Perez explains to the new recruits, they have a chance to get involved in a campaign to remedy the systemic inequalities in the Philadelphia public schools—inequalities that place them, as students of color in a rough area of the city, at a disadvantage.

The students begin to list the problems they see in their schools on a daily basis. For one, their shared building, built in the 1920s as an all-girls school, lacks sports facilities. The Kensington small schools share a building and some facilities, but little else, it seems. Students at the YUC meeting agree that across the board, increased collaboration between their schools is needed.

Some point out how few extracurricular activities are available to students in Kensington. “We need better tutoring programs,” one girl declares. Another student addressing her fellow students in the meeting, complains that in honors English class, “We aren’t learning anything. The structure is all wrong. She [the teacher] doesn’t know how to communicate with us.”

A veteran YUC student tells the new recruits that the small schools in Center City—a more affluent, mostly white area—enjoy privileges that the Kensington schools do not. They have curricular autonomy, for example, and the right to hire their new principals a year in advance to give them time to prepare and assimilate into the school. The Center City schools also have more control over their budget than the Kensington schools do.

Fighting for small schools

| “When Vallas came to Philly, students told him ‘We’ve had seven principals in five years and high teacher turnover, and something’s got to give.” — Helen Rowe, YUC organizer |

|---|

YUC, the new recruits learn, was responsible for the creation of Kensington’s small schools in the first place. Back in 2002, student activists from YUC traveled around the country, observing various small schools models. They then submitted a plan to Philadelphia School District CEO Paul Vallas that proposed small schools at Kensington, which at the time housed over 1,400 students.

“When Vallas came to Philly, students told him ‘We’ve had seven principals in five years and high teacher turnover, and something’s got to give,’ and they managed to get a commitment out of him for small schools,” says Helen Rowe, a YUC organizer.

Vallas accepted their plan, allowing Kensington to be broken down into the International Business and Entrepreneurship, Creative and Performing Arts (CAPA) and Culinary Arts high schools. He also committed to constructing an additional building for a fourth small school that will be oriented around social justice.

The outcome of that campaign taught YUC students about the potential impact of their organizing. William Elkins-Crosby, a senior in his third year with YUC, says, “When I first joined, I didn’t know what small schools were. I didn’t even know that they exist.” Likewise, junior Ricky Bracero, a YUC member for two years, says, “I didn’t know that kids could make a difference in school. [YUC] taught me that I could organize protests and walkouts.”

The outcome of that campaign taught YUC students about the potential impact of their organizing. William Elkins-Crosby, a senior in his third year with YUC, says, “When I first joined, I didn’t know what small schools were. I didn’t even know that they exist.” Likewise, junior Ricky Bracero, a YUC member for two years, says, “I didn’t know that kids could make a difference in school. [YUC] taught me that I could organize protests and walkouts.”

When YUC was first created sixteen years ago, founding organizers proposed that a youth representative seat be created on the Philadelphia school board. The board members “laughed them out of the room,” says Rowe. Since then, she says, YUC has “adopted a much more power-building analysis of change” and have built chapters in five Philadelphia public high schools.

As for the new recruits at the Kensington chapter, YUC’s message has clearly sparked an interest in the group. “I like the fact that the kids can be down to earth. I like the feeling that I’m participating in my school. I like that I can come somewhere and complain about what’s going on, or what’s not going on in my school,” says ninth grader Janette Rivera.

Demanding college recruitment and vocational preparation

YUC’s campaigns are tailored to fit the specific conditions at each chapter. At Olney High School in North Philadelphia, for example, YUC asked for four small schools to be created. Instead, the school board divided the school into two still relatively large schools, citing a lack of funding to implement YUC’s proposal. As a result, Olney YUC student activists “have spent the last year building a power base in the community,” says Rowe. They continue to lobby for their small-schools plan, organizing community forums to discuss the issue and meeting with local legislators.

YUC’s other chapters have pointed out similar problems. At Mastbaum Vocational Technical High School, which also has 1,400 students, YUC students are campaigning for better academic and vocational preparation. They have met with apprenticeship coordinators and have determined that Mastbaum students are not being effectively prepared for their trade apprenticeships or for regular college acceptance. YUC students at Mastbaum are also working to get local trade unions on board with their campaign.

YUC’s other chapters have pointed out similar problems. At Mastbaum Vocational Technical High School, which also has 1,400 students, YUC students are campaigning for better academic and vocational preparation. They have met with apprenticeship coordinators and have determined that Mastbaum students are not being effectively prepared for their trade apprenticeships or for regular college acceptance. YUC students at Mastbaum are also working to get local trade unions on board with their campaign.

At Edison High School, YUC activists are working to remedy the low rates of college recruitment and attendance for Edison students. Edison had the highest number of Vietnam War fatalities of any U.S. high school. It is a major hub for military recruitment, but, says YUC, not for college recruiters. As a result of YUC student campaigning, Edison students gained a commitment from the school that it will require that all students visit a college and fill out a college application before graduation. Those requirements will be implemented next school year.

The Strawberry Mansion High School chapter of YUC last campaigned to reform standardized testing procedures in the school. When relations with the principal soured during that campaign, Rowe, the chapter’s lead adult organizer, was escorted by school security out of the school and is now barred from entering.

YUC is no longer permitted to recruit or organize Strawberry Mansion students. Even YUC keychains, which organizers give out to new recruits, have been banned from the school. Rowe says Strawberry Mansion YUC students have been kept from doing things “that are protected under their first amendment rights to organize in a school and to represent the student organization that they are a member of.”

Overcoming obstacles, keeping up the fight

But while organizing at Strawberry Mansion has come to a temporary standstill, the campaign at the Kensington small schools, which began in 2002, is just coming to fruition. The students have scheduled a meeting with Vallas to state their concerns about inequities, and they will undoubtedly demand the same privileges that were granted to the Center City small schools.

But while organizing at Strawberry Mansion has come to a temporary standstill, the campaign at the Kensington small schools, which began in 2002, is just coming to fruition. The students have scheduled a meeting with Vallas to state their concerns about inequities, and they will undoubtedly demand the same privileges that were granted to the Center City small schools.

It is also clear that these organizing campaigns have deeply affected the consciousness of the students involved in YUC. Jamillah Hannibal, a Kensington eleventh grader in her first year in YUC, said that her time in the organization has sparked her interest in politics. She will continue to stay involved in activism when she goes to college: “I plan to join different political groups on campus. When you have a desire to fight for something that you need, that’s always with you.” Elkins-Crosby agrees: “I can see myself continuing this on. If I can get my voice heard, then that’s all I’m really looking for.”

In the end, says Rowe, the YUC students are fighting for better curriculum and conditions in their schools, but “what they’re getting currently is not their vision; that’s what they’re fighting to create.” Although the youth members are undeniably learning about the art and science of strategic organizing, the slow pace of school reform keeps them at an educational disadvantage. While not all YUC alumni will remain activists, says Rowe, YUC hopes that they will maintain a “deliberate, clear sense that they can take leadership and make changes and challenge injustice.”