by Barbara Cervone

SAN FRANCISCO, CA—In 1994, world-renowned chef Alice Waters teamed up with a middle school in Berkeley, California—near her famous Chez Panisse restaurant—and laid plans for an “edible schoolyard.” Two years later, students, teachers, parents and volunteers had cleared an acre of asphalt and planted cover crops. They transformed the school’s unused 1930s cafeteria kitchen into a “kitchen classroom.”

Today, The Edible Schoolyard at Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School draws over a 1,000 visitors annually. Every day, the middle school students tend the thriving acre of vegetables, fruits, herbs, and flowers, and try their hand at cooking in the kitchen classroom.

Across the San Francisco Bay, the nonprofit Urban Sprouts has worked with an ever-multiplying number of students and schools to create new and expanded school gardens in some of San Francisco’s hardest-pressed neighborhoods economically. As hoped, these young urban gardeners are adding fresh produce to their diet—foods they once swore they would never eat. But they are learning other things, too. Students told the program’s evaluators:

Across the San Francisco Bay, the nonprofit Urban Sprouts has worked with an ever-multiplying number of students and schools to create new and expanded school gardens in some of San Francisco’s hardest-pressed neighborhoods economically. As hoped, these young urban gardeners are adding fresh produce to their diet—foods they once swore they would never eat. But they are learning other things, too. Students told the program’s evaluators:

- “I learned that we should take more care of the environment.”

- “I’m worried about chemicals and stuff in the water, there’s only one earth, and it’s sad because we live here and I don’t want to be living on Mars.”

- “I like fruits and vegetables more.”

- “Organic food actually tastes better and it’s more natural.”

- “In the garden, I learned to grow up and be a successful person.”

- “I do better in school now because my body is not being energized with Cheetos, it’s being energized with lettuce.”

Several years ago The National Gardening Association started an online registry of school gardens across the country, and over 1,200 schools have registered—a number that grows weekly—allowing school gardeners to link up with each other and compare notes.

Soldiers of the soil

The idea of school gardens may seem fresh, but it is decidedly old. The movement began in the U.S. in the 1890s, with advocates agreeing on the inherent value of school gardens but disagreeing on their goal. Some saw school gardens as a way to beautify schools and civic space, while others embraced them as a way to “Americanize” immigrants. Some extolled school gardens for improving dietary and health practices. Others dreamed of recapturing America’s agrarian past. Among educators, some saw gardens as a way to teach science or provide vocational training; others spoke of how school gardens might enrich academic subjects across the board.

The idea of school gardens may seem fresh, but it is decidedly old. The movement began in the U.S. in the 1890s, with advocates agreeing on the inherent value of school gardens but disagreeing on their goal. Some saw school gardens as a way to beautify schools and civic space, while others embraced them as a way to “Americanize” immigrants. Some extolled school gardens for improving dietary and health practices. Others dreamed of recapturing America’s agrarian past. Among educators, some saw gardens as a way to teach science or provide vocational training; others spoke of how school gardens might enrich academic subjects across the board.

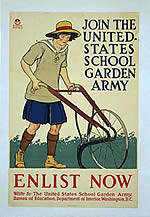

In World War I and II, school gardens became linked to national security—with slogans like “food will win the war.” As Urban Sprouts blogger Abby Jaramillo writes: “The U.S. School Garden Army enlisted ‘soldiers of the soil’ to grow food at schools, to increase fruit and vegetable consumption, and to improve the health of the populace.” During World War II, several million school children grew food in their school gardens, reportedly growing 40 percent of all fruits and vegetables eaten in the United States.

As schools burst at their seams in the post-war era—thanks to the first round of “baby boomers”—one school garden after another gave way to playground and classroom expansions. They disappeared without a trace.

Imagining what is possible

Delightfully, once again, soil is replacing asphalt in some schoolyards.

Delightfully, once again, soil is replacing asphalt in some schoolyards.

“Do you think we really could grow enough vegetables and fruit for the students at our school—and the neighborhood, too?” asks Adam, a seventh grader at the Lighthouse Community Charter School in Oakland, California. He and his classmates are sorting lumber—the first steps to transform a corner of their school playground into a collection of raised garden beds. “That would be awesome.”

“I can already smell the broccoli,” Tyler quips

“I’m a fast food junkie,” Maria admits. “But my dad has diabetes and he says I have to change what I eat—or I’ll die or something.”

“Maybe instead of being Generation X or something,” says Hector, “we’ll become the Healthy Foods Generation. Right across the street, you can get every kind of fast food you’d ever want. What if instead of spending money there, we grew our own food here?”

Indeed, what would happen if school gardens came back with the force they once had, when policymakers and the citizen at large saw them as part of our national well being?

“Just imagine,” says Jorge, an Oakland seventh grader.

RESOURCES AND LINKS

California School Garden Network

CSNG represents a variety of state agencies, private companies, educational institutions and nonprofit organizations dedicated to creating and sustaining gardens in every willing school in California. The Network serves as a central organization to distribute school garden resources and support throughout the state, although many of its resources would be helpful to school gardeners nationwide. The Network’s mission is to create and sustain California school gardens so as to enhance academic achievement, a healthy lifestyle, environmental stewardship, and community and social development.

Garden-based Learning Videos

This blog entry points visitors to the Victory Grower website, which supports gardening as an excellent way to increase food security (the amount and quality of food) in America. Links lead to videos and other media documenting historical gardening efforts that have made a real difference in American life, including Liberty and Victory Garden programs and the U.S. School Gardening Army.

Kids Gardening

Sponsored by the National Gardening Association, this website offers a searchable index of school gardens across the country, classroom projects, grant opportunities, curriculum guides on topics ranging from hydroponics to pollination, online teacher courses, and more.

Life Lab

Life Lab Science Program has been working in the field of science and environmental education since 1979. With curricula and programs, the organization helps schools develop gardens where children can create “living laboratories” for the study of the natural world. Since developing the first Life Lab school garden in Santa Cruz in 1978, Life Lab has worked with over 1,400 schools across the United States training tens of thousands educators.

School Garden Wizard

School Garden Wizard was created for the K-12 school community through a

partnership between the United States Botanic Garden and Chicago Botanic Garden. The website is divided into five sections: make the case, plan for success, create the garden, learn in the garden, and keep it growing.

The Edible Schoolyard

The Edible Schoolyard (ESY), established in 1995, is a one-acre garden and kitchen classroom at Martin Luther King, Jr. Middle School in Berkeley, California. It is a program of the Chez Panisse Foundation, a nonprofit organization founded by chef and author Alice Waters. The garden started as a cover crop in a vacant lot with once-monthly student participation. More than a decade later, it is a thriving acre of vegetables, fruits, herbs, and flowers. The program hosts over 1,000 visitors each year—from educators, to health professionals, to international delegates—and has inspired countless kitchen and garden programs, including a small network of Edible Schoolyard affiliate programs in cities across the country.

Urban Sprouts School Gardens

By cultivating school gardens in San Francisco’s underserved neighborhoods, Urban Sprouts partners with youth and their families to build eco-literacy, equity, wellness, and community. Activities include school gardens and nutrition education, a farmers-in- residence program, an intensive summer gardening and leadership program for youth, and a garden-based education model and training initiative, now spreading to other states in the West.